by Winding Pathways | Jun 27, 2024 | Nature, Trees/Shrubs

This is a story of the serendipity of giant trees. On a recent long drive to New Jersey, we planned to visit a grove of giant white pine trees in Pennsylvania’s Cook Forest State Park. Plans don’t always go perfectly, but sometimes serendipity happens. It sure did for us.

We are awestruck by the beauty and heritage of giant trees and found an exceptional one by accident. Serendipity. About a hundred miles after we left home, we needed to change drivers and exited Interstate 80 Eastbound just after crossing the Mississippi River.

Rest Stop Serendipity

Welcoming Oak

We planned to make a brief stop but stayed a while to marvel at a massive white oak that greeted us at the building’s entrance. We marveled at its girth and spreading limbs. The people who designed and built the restroom structure took pains to carefully craft it to emphasize the tree’s beauty and protect it from construction damage.

This tree is worth a stop. It is at about I-80’s exit one in Illinois immediately south of the Mississippi River. There’s also a magnificent view of the River and Iowa in the distance.

Pennsylvania Wilds Serendipity

We’d checked Pennsylvania’s predicted weather before leaving our Iowa home, and it promised pleasant camping weather in Cook Forest State Park. Our camping gear was in the car as we headed East. Well, weather reports aren’t perfect. Crossing Ohio in driving rain we realized that being in a tent that night would be soggy, but serendipity happened. Our cell phones helped us book an overnight room at a lodge near the Park’s ancient pine grove.

In the rain, we took small twisty roads for about 20 miles north of Clarion, Pennsylvania.

It was still cascading down as we entered the vast park in the midst of THE PENNSYLVANIA WILDS. We’d come a long way and were determined to see the grove of ancients, so, raincoat-clad, we headed up the trail.

Cook State Forest Serendipity

It was magical. We were enveloped in a forest of massive pines that had sprouted around 1600 and bypassed by the loggers who leveled most of the Keystone State’s forests. Beneath the trees, the ground was soft as a plush carpet. Other than raindrops, silence enveloped us – a soothing respite from the Interstate’s noisy trucks.

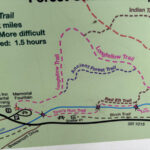

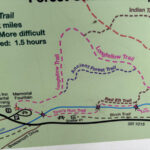

Cook Forest State Park is set in a vast woodland along the Clarion River. Only a few miles north of Interstate 80, it offers hiking, mountain biking, fishing, hunting, river running, and enjoying massive trees. Many area cabins and lodges offer dry places to overnight, and the Park has a campground. Serendipity met us again.

-

-

Map guidance

-

-

Giant forest

-

-

Walking in the rain

Clarion River Lodge Serendipity

Wet and soggy after our forest walk, and tired of twisty roads, we found ourselves at the Clarion River Lodge near the grove where Shannon Otte warmly greeted us. She showed us our cozy, dry room. Later we enjoyed dinner while watching the rain continue to drench the woods.

-

-

We arrived soaked…

-

-

Rustic and comfy.

-

-

One of the warm features of The Clarion Lodge.

Fortunately, the rain slowed, giving us a chance to walk a gravel road above the lodge. Ovenbirds serenaded us from deep in the forest as we overlooked the Clarion River.

The Clarion River Lodge is a revitalized lodge with distinctive rooms creatively well-appointed. The dining area and bar welcome guests and locals. The entire establishment, tucked into the woods is cozy and comfortable. The mix of vintage and modern make for great exploring of the common room and the halls, and peeking into different rooms.

-

-

Beautiful Quilt

-

-

A blend of old and new.

-

-

The Throwback Record Room

-

-

Light and Airy

The next morning, we took advantage of the coffee maker in the lobby and enjoyed the view of the woods and moss-covered rocks from the end of the second-floor hall porch. A phoebe scolded us as we sat sipping our warm beverage. When we realized we were settled near its nest we moved further away. Under a clear blue sky and waning crescent moon, we enjoyed the soft drip of last night’s rain off the trees.

-

-

Visitors can enjoy several types of lodging in the Pennsylvania Wilds

-

-

A quiet interlude

-

-

Sparkling after the rain.

Overall the drive East was filled with Giant Trees that enticed us to stop.

Finding Giant Trees

American Forests keeps a list of the biggest known individual of nearly all species of North American Trees. The registry helps anyone locate these giant and, often, ancient trees.

by Winding Pathways | Aug 31, 2023 | Geology/Weather, Travel/Columns, Trees/Shrubs

Travels this summer showed how varied the North American continent’s vegetation, landscape, and weather are. Most recently we have journeyed from New Jersey to Southern Saskatchewan. Vegetation and terrain could not be more different.

Venturing from “Wide Open Spaces” to “Into the Woods”

Native forbs and grasses cover the land.

The Dixie Girls’ refrain “Wide Open Spaces” describes the terrain we drove through in Southern Saskatchewan. One day Rich hiked to a high spot in Grasslands National Park. Beneath and beyond him were thousands of acres of grasslands – forbs and native grasses. Nary a tree poked upward in this vast and beautiful land.

Brook waters tumble over rocks.

In contrast “Into the Woods” by Sondheim and Lapine would better characterize the roadside woods as our car approached New Jersey six weeks later. Jersey’s woods are so dense and thick that little sunlight filters through the leafy crown. On wood edges, impenetrable tangles of shrubs, brambles and vines seem to be everywhere.

Goldilocks Zone

Iowa’s woodlands tend to be more open than eastern woods.

True to its location in “middle America,” our home in Eastern Iowa fits somewhere in between. You might say it is the “Goldilocks Zone” of vegetation. Midwestern woods tend to be more open than New Jersey’s but dense compared with Saskatchewan’s few low brushy areas. Iowa’s neither wide open nor dense but somewhere in between. It’s like a hybrid.

Location, Location, Location

What makes such a striking difference in vegetation extremes? These numbers tell part of the story:

Location Annual Precipitation Annual Mean Temp Wind

Saskatchewan 14” 39 F often and strong

New Jersey 54” 48 F calm to light

Iowa ranges in the middle with an average of 36” of precipitation.

Numbers don’t tell it all. New Jersey’s climate is moderated by the ocean, so the hottest temperature ever recorded near Rich’s hometown of Denville was 104 degrees Fahrenheit, and the coldest was -21. That’s a 125-degree variance. In Val Marie, Saskatchewan, the highest temperature ever recorded was 113 degrees Fahrenheit, and the lowest was -70. That’s a whopping 183-degree variance.

When we visited Val Marie, Saskatchewan, on the summer solstice, the sun was brilliant, the breezes gentle, and the night air cool. Sunsets lingered and the moon seemed to pop over the horizon and grace the landscape all night. Recently, thick smoke from wildfires blanketed the province like it has in Iowa and temperatures soared.

We hit New Jersey just right with warm day temperatures, a slight south breeze, tolerable humidity, and evenings that cooled down. The wildfire smoke had moved out. We were fortunate both times.

There’s more

Saskatchewan is much further north than New Jersey, so it receives significantly more summer light and much less sunlight in winter. Generally, Saskatchewan enjoys low humidity, while Jersey sweats in humid air year-round.

These differences in light and temperature plus topography, soil type, and the way people manage the landform its appearance and determine what species of plants and wildlife can exist there.

We noticed that people who live in the thickly wooded East are sometimes uncomfortable when traveling in the West’s wide-open spaces and Westerners feel claustrophobic amid the thick growth in the East. Comfort levels vary with the terrain.

Commonality

Both Saskatchewan and New Jersey do share a common feature. Rocks! Everywhere are pebbles, rocks, and boulders. Saskatchewan was glaciated and rocks, carried in by sheets of ice, litter the fields. Piles dot the fields where ranchers and farmers have piled them so they can till the sandy-type soil. New Jersey’s rocks are often bedrock with glacial striations and miles of rock and stone walls.

-

-

Lichen-covered boulders

-

-

New Jersey’s inland landscape is defined by boulders.

What’s the difference between a rock wall and a stone wall? Well, there really isn’t. Both are made of rocks. But some, like rounded glacial rocks, were hauled from fields and tossed into rows to make boundaries. It takes a lot of work to maintain them. As Robert Frost stated in one poem, “Good fences make good neighbors.”

Others, flatter rocks like slate and shale, are easier to fit together. Marion’s dad was a stone worker crafting rock walls, carefully choosing rocks to fit well together. These rock walls stand for decades. At any rate, both Saskatchewan and New Jersey have an abundance of rocks that influence how land is used.

One of our traveling pleasures is noting vegetation and topography through our car’s windows, even as we speed along. To us, all places are interesting, and no matter what the terrain and vegetation we’re passing through it’s fascinating.

by Winding Pathways | Aug 10, 2023 | Mammals, Nature, Trees/Shrubs

Squirrels: Free Tree Planters

Our neighborhood squirrels proved they are the best tree planters.

We lost most of our mature trees in the 2020 Derecho.

An August 2020 derecho tore through Iowa pushing 140-mile-an-hour wind against trees and buildings. Trees by the hundreds of thousands tumbled to the ground. Winding Pathways wasn’t spared. We lost most of our firs, oaks, hickories, and cottonwoods. The devastation in nearby Faulkes Heritage Woods was even worse.

Almost immediately, shocked people took action. Government forestry departments, aided by tree planting nonprofits, and private citizens unleashed their shovels and planted thousands of trees. So did the squirrels. Well, not really. People planted trees.

Squirrels bury nuts in caches to retrieve them later.

Squirrels planted nuts and acorns.

Then three seasons of drought followed. Once planted, most trees were not tended as they need to be. So, many human-planted trees shriveled in the heat and dryness, while the nuts buried by squirrels sprouted and the new trees were flourishing.

But why?

We have theories. A human-planted tree seedling needs plenty of moisture to keep its trunk and new leaves hydrated. Sparse roots must pull water from the ground and send it upward. That’s a tough job in a wet year. Come drought it’s nearly impossible.

Squirrels did better. These industrious rodents don’t mean to create new trees. They’re simply storing nuts underground so they have enough fat and protein-rich food to tide them through winter. All they need to do is dig up a nut when hunger calls. Squirrels overfill their larder, burying more tasty nuts than they’ll ever need. Unfortunate squirrels are eaten by hawks, foxes, owls, or humans, but the nuts they’d buried remain patiently waiting for spring’s warmth to germinate.

Sprouting nuts grow roots able to pull scarce moisture from the soil and send it to new baby leaves poking through the ground.

As we walked through July 2023’s dry woods we sadly see human-planted trees shriveled up and dead, while nearby a new generation of tiny walnut, oak, and hickories is rising from nuts planted by industrious squirrels.

-

-

Newly planted trees need watering.

-

-

This squirrel planted walnut seedling sprouted just this year in spite of the drought.

Squirrels Don’t Plant All The Trees

Squirrels are the best friends of nut-bearing trees, but other tree species can’t rely on the furry rodents. Cottonwoods, for example, produce millions of seeds too tiny for squirrel food. So, the trees grow cottony fluff that floats seeds to distant places. If one lands in a patch of moist bear soil a fast-growing cottonwood sprouts. Maples have helicopter-like seeds that whirl a gig away from the parent to sprout a ways away.

Pity the poor Osage Orange tree that grows huge citrus-smelling balls containing hidden seeds. Many folks call them hedge apples. A tree must get its seeds away from its own shade. Squirrels do the job for oaks. The wind for cottonwoods. Massive mastodons once munched on Osage Orange hedge apples, wandered off, digested the pulp, and pooped out the seeds. When these massive elephants went extinct the tree lost its partner and saw its native range shrink from much of North America to a tiny spot down south.

Nature provides many ways for trees to reproduce and the results are often superior to what humans can do. We appreciate the squirrels that plant nuts many of which sprout into healthy native trees. Thanks, squirrels!

by Winding Pathways | Jul 6, 2023 | Nature, Trees, Trees/Shrubs

Just what impact did the heavy wildfire smoke that blanketed vast regions of Canada and the United States have on plants? We wondered. The news media warned of smoke’s impact on people and pets and cautioned us to stay indoors and limit physical activity. But what about plants?

For many June days smoke from Canadian fires settled over Winding Pathways and a vast area of North America. With the Western United States likely to ignite later in the summer, it’s time for Smokey Bear to get ready for more action these growing-season days.

-

-

Air quality is compromised by smoke. Photo credit NP

Impact on Photovoltaics

We watched the real-time production monitor on our photovoltaic system during smokey days. It indicated that smoke was reducing our collector’s ability to turn solar energy into electricity. Was something similar happening with crops, trees, and lawns?

We turned to wildfire and smoke experts at our alma mater, the University of Idaho’s College of Natural Resources, for answers.

Smokes filters light.

Dr. Charles Goebel, Professor of Forest Ecosystem Restoration, explained, “Yes, smoke can impede photosynthesis. There is some research that indicates that short-term smoke exposure can reduce photosynthesis by as much as 50%. This is, in part, due to the reduced light intensity, destruction of chlorophyll, and reducing the flow of carbon dioxide through stomata.” He added that lower levels of smoke can help plants by increasing the carbon dioxide level and diffusing the light that some plants use better than direct sunlight.

How Plants React to Smoke

Dr. Goebel added fascinating aspects about plants and smoke. “Plants can filter out some smoke particles but probably not enough to make much difference during heavy smoke events. Smoke particles that settle to the ground may have some beneficial impact on plants. Smoke contains calcium, magnesium, and potassium, which are essential plant nutrients,” he added.

Wait…There Is More!

Wildfires are common in the West.

Dr. Lena N. Kobziar, Associate Professor of Wildland Fire Science, added: “We know that fires emit microbes (fungi, bacteria, archaea) along with other gaseous and particulate matter. Smoke transmits these living microbes that can colonize damaged soil and begin to grow and multiply. This can help the soil,” she said.

Want to learn more? Dr. Kobziar’s Fire Ecology Lab website has an enormous amount of current information on wildfires and their impact on forests and people.

The University of Idaho

We’re Vandals……meaning graduates of the University of Idaho. Our immediate family earned four degrees there. We’ve joke that the “real” U of I is not in Iowa City but in Moscow, Idaho. The Vandals are its mascot.

We enjoyed our academic careers at the U of I. Knowledge gained there helped our lives and careers and we humbly thank its faculty for continuing to answer our nature-related questions, like about smoke, years after graduation.

It’s a great institution. Take a look at the University of Idaho’s website. Go, Vandals!

by Winding Pathways | Feb 2, 2023 | Foraging, Nature, Pests, Trees, Trees/Shrubs

Disappearing Ash Trees

Ash trees are fast disappearing from American forests and towns. It’s tragic.

There are several ash species, including white, green, blue, and black. A Chinese native insect, the Emerald Ash Borer, is killing them all quickly. It’s awful.

Years ago, Dutch Elm Disease cleared cities of American elms, and many homeowners and towns planted green and white ash trees to replace them. Ashes, in general, thrive in the woods and towns. They grow relatively quickly, resist storm damage, and are beautiful. They seemed like an ideal urban tree.

That was true until Emerald Ash Borers were found in Michigan in 2002, although they may have been around at least a decade earlier. Since then, the insect has spread like crazy, killing ashes radiating outward from Michigan.

They reached Iowa years later and have since killed most of the trees in Cedar Rapids, area woodlands, and many other towns.

Salvaging Ash trees

Rich salvages wood from a scrap pile of used pallets. Pallets are made from cheap wood, like cottonwood, poplar, and hackberry, but now he’s finding ones made of ash.

Loggers are salvaging dead and dying ash trees, and the wood is cheap, at least for now. Soon ash lumber will no longer exist.

A Versatile Wood

Sports fans will miss ash wood. It makes the best baseball bats and has been used for gymnastic bars.

Ash also is crafted into gorgeous furniture.

We lost our big ash tree in the August 2020 derecho, but it was already infested with borers with its days numbered. Sadly, we cut the tree up but gave it a second task. It harvested solar energy and used it to make wood. That wood is now being fed, piece by piece, into our woodstove. It’s keeping our home warm, but we’d rather have our tree.

-

-

Ash bat on oak floor.

-

-

The ash tree anchored our east corner of the property.

-

-

White Ash bats will soon be a memory as these elegant trees die.

by Winding Pathways | Jan 5, 2023 | (Sub)Urban Homesteading, Garden/Yard, Nature, Trees/Shrubs, Weeds

A raging blizzard roaring over Winding Pathways just before Christmas showed us the power of HARVESTING SNOW. We love catching it.

Well, we didn’t really catch the snow, but our prairie did. It has a talent for harvesting snow and other forms of moisture. It taught us how prairie and other taller plants – grasses, forbs, shrubs, vines, and trees – help themselves grow next summer.

Our prairie has a thick growth of two-foot-tall dead stems from last summer’s growth. Each stalk is brittle, but thousands of them working together slowed the wind just enough for it to drop the snow it had swept off nearby lawns and roads.

The deep drift that settled on our prairie will melt and give next spring’s plants a jumpstart in moist soil. Nearby shortly sheared lawns can’t catch snow and will start the spring on dryer soil. Nature delivered irrigation water to our yard for free!

Nature’s Wisdom in Harvesting Snow

Growing up in the East, we are used to Nor ‘easters that pummel the landscape and create great skiing conditions. Until we moved west, we were not so familiar with how nature replenishes soil moisture, well, naturally!

In dry areas snow also helps next summer’s vegetables. During college, Rich worked weekends at an Idaho ranch. He was surprised one January when Lucille Pratt, part owner of the land and an outstanding vegetable gardener, asked him to shovel snow from a nearby drift onto the garden.

For a Jersey boy, this seemed like a weird request, but melting snow oozed water into the soil. That helped get the vegetables going and sustain them through the dry summer.

Snow may seem like a bother but it’s also a blessing to dry soil and the plants it sustains.

Over two blizzardy days, our prairie gently caught snowflake after snowflake. We already are looking forward to bright prairie flowers dancing in next summer’s breeze. Thanks, prairie for harvesting snow. Nature’s wisdom to catch winter’s snow and help next summer’s growth is amazing.

-

-

Capturing snow.

-

-

Three days later, a rapid melt left the ground bare, except where prairie plants held snow.