by Winding Pathways | Dec 7, 2023 | (Sub)Urban Homesteading, Birds, Nature

Why do Birds Fly Into Windows?

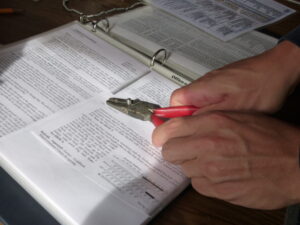

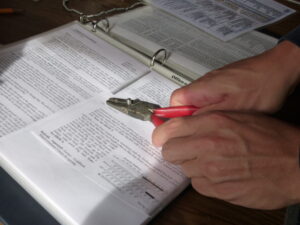

The spray makes the window opaque.

Windows, deadly for birds. According to the National Audubon Society, about one billion birds are killed every year when they crash into windows. About half collide with low commercial building windows with the rest crashing into home windows. Surprisingly few seem to crash into the high windows of skyscrapers.

Birds fly into windows because they just don’t see them and assume they’re about to zip through safe soft air. Sometimes they may see reflections of vegetation behind them and think they are zooming to a convenient perch.

How to Help a Bird

When Rich was director of the Indian Creek Nature Center, he’d often get calls from upset people who had just found a quivering bird beneath their window. In his experience one of two outcomes is likely. Either the bird will soon die or it will fully recover and fly off. He suggests leaving the bird alone for at least an hour unless it’s likely to fall prey to a hungry neighborhood cat. In that case, it is probably best to gently place it in a cardboard box to give it a chance to recover…or die.

Unfortunately, there’s no effective first-aid technique to reverse death. Hopefully, the bird will soon recover and speed away. If not, a respectful burial is in order.

Tips

Here are some tips from the Portland, Oregon, Audubon Chapter of the National Audubon Society for reducing window collisions:

- Place bird feeders away from large windows.

- Avoid putting house plants immediately inside windows. Birds may see them and attempt to fly to a perch.

- Put stickers/decals on the outside of windows. (Note: Many sources recommend these. Stickers can be bought online or at bird-feeding stores……but we, at Winding Pathways, have not found them very effective.

- Stretch netting across the outside of the window to physically keep birds from crashing. We’ve found this best on windows that experience frequent bird collisions.

- Put colorful tape on the outside of the windows.

- Douse outside lights. Come sundown our nation is way over-lit. Lights block viewing the magnificent night sky while often disorienting migrating birds.

We Can Help

Songbirds face many challenges in our modern world. They crash into windows, hit poles, get gobbled up by house cats, and are confused by electric lights. They need all the human help they can get to stay alive and healthy.

by Winding Pathways | Apr 27, 2023 | (Sub)Urban Homesteading, Birds, Nature

Sometimes we feel sorry for Lonely Louie, so sorry that we toss him a scoop of corn.

Flocks of wild turkeys have been visiting our yard almost daily for years. Most often we see gobbler groups. They are adult males with long beards and spurs. Once in a while a group of hens stops by to glean seeds under our bird feeders. They are sleeker than males and lack a beard. And, rarely, hens appear with a clutch of poults. An exciting event indeed!

-

-

A dozen or so males routinely visited the yard.

-

-

Rarely we would see hens with young.

About two years ago a threesome of males began visiting every day. Sometimes two or three times a day. We called them Huey, Duey and Louie. They seemed inseparable, and we never saw them alone. Late evenings we sometimes watched them flap up to tall tree branches to roost for the night.

Huey and Louie

Then, only two visited. Huey and Louie. We never learned what happened to Duey. Maybe a predator enjoyed him for a meal. Or, he may have had an accident. It is a mystery, but we continued enjoying visits by the other two.

Lonely Louie looks for corn

One day Louie showed up alone. We haven’t seen his companion since. Lonely Louie is now trully a loner. If he’s in the yard and a flock of turkeys appears Louie stays away. He seems shunned by the others. Maybe he’s just shy.

He seems to miss his two friends. So do we, but we enjoy seeing Lonely Louie and know he appreciates the scoop of corn we toss out when he arrives.

by Marion Patterson | Apr 13, 2023 | Amphibians/Reptiles, Birds, Flowers/Grasses, Hearing, Nature, Wonderment

A Season of Variables

After a drab March “look up, look down, listen” season is here. It’s exciting and frustrating. Always something to see and hear and things we miss, too.

What is look up, look down, listen? Well, when we walk in woods and prairies, we’re always attuned to nature’s beauty and curiosities. In the Northern Hemisphere April and May force challenges and delights, as the earth turns toward the sun. Its warmth stimulates new life while welcoming arrivals from down south.

Here in Iowa, like much of the United States, bird migration rises through April and peaks in early May. Woods, wetlands, and prairies are filled with bird species we haven’t seen since last year.

Look Up!

“Look up,” Marion remarked on one April walk last year. She spotted the first Rose Breasted Grosbeak of the season. He was perched on a thin branch high in a sycamore tree. As we walked along, we kept looking up to spot other new arrivals. They added color and song to those of cardinals, chickadees, and woodpeckers who are our neighbors all year.

-

-

A catbird drinks by a pool.

-

-

The brown creeper blends in with tree trunks.

Look Down!

After admiring the Grosbeak and moving on, I said, “look down.” We had been paying so much attention to birds up in the trees that we almost trampled a Dutchman’s Breeches, a delicate white wildflower with petals shaped like old-time Dutch pants. Looking down revealed spring beauties, Mayapples, hepatica, and anemones. Some were not quite in bloom and a few had gone by, but most were in their spring glory.

-

-

Early spring flowers

-

-

Reaching for the sun

-

-

Dutchman’s Britches

-

-

Snow Trillium

Shhhh! Listen

Passing a low wetland, we both paused to hear the songs of the chorus frogs and peepers that greet listeners each spring between the vernal equinox and Easter.

So, what do we do on a spring walk? Look up or down or listen? All of these. It is the best time of year to enjoy beauty clinging to the soil, singing from treetops, and chorusing from ephemeral pools.

Make Nature ID easier with Apps

Spotting birds hiding invisibly in tangles of branches and vines is challenging. What’s in that thicket singing? Thanks to the Cornell Laboratory of Ornithology, we turn on our Merlin app, point the phone where the songs originate, and learn who’s singing. Merlin is easy to download from the app store. Sometimes we are lucky and watch migratory birds close at hand.

Some people even lure birds in with treats that are eagerly consumed by arriving birds.

Wildflowers cannot hide but can be confusing. We sometimes use an app called SEEK to identify ones that are mysterious to us. SEEK is also easy to download from the app store and can also help identify trees, weeds, and other living things.

Look up, look down, listen! season may be the very best time to be outside. We love it.

by Winding Pathways | Apr 6, 2023 | Birds, Nature

Yellow-bellied sapsuckers are precise timers. Every late March we look for this gorgeous, yet sometimes hard-to-spot, migrating bird. They visit our woods in April on their way to northern breeding areas.

Weather Conditions

Late March and April nights are often below freezing, followed by warm days. That temperature fluctuation stimulates maples to send sap upward. At the same time, the warmer days awaken hungry insects seeking sweet meals. Yellow-bellied Sapsuckers arrive from the south at sap time and make their familiar wells, or small rows of holes, through maple bark. Sap oozes out and attracts protein-rich insects. Hungry migrating sapsuckers dine on both sweet sap and tasty insects.

Yellow-bellied Sapsuckers are Precise Timers

Yellow-bellied Sapsuckers time their migration precisely. They arrive exactly when conditions are perfect. Within a few weeks the weather warms, maples stop bleeding sap, insects disperse, and the birds are north of us getting ready to nest.

-

-

Insects are attracted to the sap weeping from maple trees.

-

-

sapsuckers time their arrival well.

by Winding Pathways | Mar 16, 2023 | (Sub)Urban Homesteading, Birds, Nature

Tree Sparrows. Two species. What could be more confusing? Well, there’s more. Both look like common House Sparrows (formerly known as English Sparrows.

Meet the American Tree Sparrows

Marion glanced at our feeders recently and noticed what looked like a Chipping Sparrow in the midst of a flock of House Sparrows. But it wasn’t. It was an AMERICAN TREE SPARROW. This bird nests in far northern Canada and is almost always spotted in winter. Why it doesn’t keep flying south and winter somewhere warmer than Iowa is a mystery to us. The bird does look like a Chipping Sparrow, but it’s bigger and “chippers” left long ago to winter where it’s warmer. We won’t see one again for a few months. So, a rusty capped sparrow in winter stands a good chance of being an AMERICAN TREE SPARROW.

Meet the New Tree Sparrows

Rich looked out the window a few days later and spotted an odd bird. It was near House Sparrows but looked slightly different. A dark spot on its cheek revealed it as a EURASIAN TREE SPARROW. What was it doing in our Iowa yard?

Back in 1870 a box of wild birds arrived in St. Louis from Germany. Inside were 12 Eurasian Tree Sparrows that were released. They slowly spread outward.

According to the Cornell University Laboratory of Ornithology’s ebird the bird spread north slowly and took about 150 years to reach our yard. It’s been widely spotted across the United States, but mostly along the Mississippi River.

Differences in Habitat Preferences

It looks like a House Sparrow at a quick glance. House Sparrows are at home in urban areas while the European Tree Swallow is more a denizen of brushy areas outside town. Sometimes they mingle. See a flock of House Sparrows. Take a close look. One may be a European Tree Sparrow.

European and American species share one trait. Both prefer feeding on the ground. Why they’re called tree sparrows beats us.

Learn More!

For accurate information on birds check out the Lab of Ornithology’s website.

-

-

Chipping Sparrow

-

-

House Sparrow

-

-

Can you find the sparrows?

by Winding Pathways | Dec 15, 2022 | Birds, Garden/Yard, Nature

A chickadee gently cradled in man’s hand.

On an early, warm, bright November day, several Coe and Mt. Mercy University Students with their professors arrived at Winding Pathways to band birds. They stood mesmerized as one cradled a diminutive bird in his hand. This long-distance traveler had met a temporary misfortune.

It was a golden-crowned kinglet, a tiny bird tipping the scales at only .19 ounce. On a recent night, it had winged south from its summer home in the north and decided to rest and feed amid the tall grass and woods at Winding Pathways. Then, it would continue southward. It didn’t know that Dr. Neil Bernstein had other plans.

-

-

Dr. Bernstein sets a mist net by a fallen log.

-

-

trapped chickadee

-

-

Untangling bird

Neil had stretched mist nets an hour earlier. The kinglet, along with chickadees and a Carolina wren didn’t see these fine mesh nets in time. They were caught but uninjured. Neil showed the students how to band birds by gently removing them from the net, weighing each tiny bird, recording data, placing a small lightweight band around its leg, and releasing it. Data are then submitted to help researchers better understand bird migration.

The kinglet and wren waited patiently as students weighed and banded each, but not the chickadees. These bitty, year-round residents have an attitude. They didn’t like being held one bit and pecked at the student’s fingers.

-

-

A bird’s claws poke through the bag.

-

-

Verifying information is important.

-

-

Tiny band ready to attach to a bird

-

-

Checking feathers

Student Reactions

Students were used to collecting scientific data on different natural topics. They were fascinated by the process of banding birds. “I thought we were going to listen to a bird band!” joked one student. Another envisioned running around chasing birds, concluding that would not work well.

Students commented on how the pecks were sharp but not worrisome. One explained she talked quietly to the chickadee as she carefully held it. Reassuring the bird, she would not hurt it. “I could feel its heart rate slow down,” she commented.

Although chickadees are small, kinglets are even smaller. This kinglet will carry its band as it wings southward but chickadees are homebodies and will wear their bands as they flit around our yard all winter.

Why Band Birds?

Tiny band with a number.

Banding is a traditional way of learning where birds go, habitat needs, and the impact of climate on both. Perhaps a fellow bander will catch “our” kinglet and inform scientists at the US Geological Survey.